Antiochus III the Great

| Antiochus III the Great | |

|---|---|

| Seleucid King | |

|

|

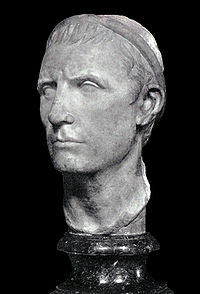

| Bust of Antiochus III | |

| Reign | 223 BC - 187 BC |

| Born | 241 BC |

| Birthplace | Babylon, Mesopotamia |

| Died | 187 BC (aged 54) |

| Place of death | Susa, Elymais |

| Predecessor | Seleucus III Ceraunus |

| Successor | Seleucus IV Philopator |

| Consort | Laodice III |

| Father | Seleucus II Callinicus |

| Mother | Laodice II |

Antiochus III the Great (Greek: Ἀντίoχoς Μέγας; ca. 241–187 BC, ruled 222–187 BC), younger son of Seleucus II Callinicus, became the 6th ruler of the Seleucid Empire as a youth of about eighteen in 223 BC. Ascending the throne at young age, Antiochus was an ambitious ruler. Although his early attempts in war against the Ptolemaic Kingdom were unsuccessful, in the following years of conquest Antiochus proved himself as the most successful Seleucid King after Seleucus I himself. His traditional designation, the Great, reflects an epithet he briefly assumed after his Eastern Campaign (it appears in regnal formulas at Amyzon in 203 and 202 BC, but not later). Antiochos also assumed the title "Basileus Megas" (which is Greek for "Great King"), the traditional title of the Persian kings, which he adopted after his conquest of Coele Syria.

Contents |

Early years

Antiochus III inherited a disorganized state. Not only had Asia Minor become detached, but the easternmost provinces had broken away, Bactria under the Greek Diodotus of Bactria, and Parthia under the nomad chieftain Arsaces. Soon after Antiochus's accession, Media and Persis revolted under their governors, the brothers Molon and Alexander.

The young king, under the baneful influence of the minister Hermeias, authorised an attack on Judea instead of going in person to face the rebels. The attack on Judea proved a fiasco, and the generals sent against Molon and Alexander met with disaster. Only in Asia Minor, where the king's cousin, the able Achaeus represented the Seleucid cause, did its prestige recover, driving the Pergamene power back to its earlier limits.

In 221 BC Antiochus at last went east, and the rebellion of Molon and Alexander collapsed which Polybios attributes in part to his following the advice of Zeuxis rather than Hermeias.[1] The submission of Lesser Media, which had asserted its independence under Artabazanes, followed. Antiochus rid himself of Hermeias by assassination and returned to Syria (220 BC). Meanwhile Achaeus himself had revolted and assumed the title of king in Asia Minor. Since, however, his power was not well enough grounded to allow an attack on Syria, Antiochus considered that he might leave Achaeus for the present and renew his attempt on Judea.

Early wars against other Hellenistic rulers

The campaigns of 219 BC and 218 BC carried the Seleucid armies almost to the confines of Ptolemaic Egypt, but in 217 BC Ptolemy IV confronted Antiochus at the Battle of Raphia and inflicted a defeat upon him which nullified all Antiochus's successes and compelled him to withdraw north of the Lebanon. In 216 BC Antiochus went north to deal with Achaeus, and had by 214 BC driven him from the field into Sardis. Antiochus contrived to get possession of the person of Achaeus (see Polybius), but the citadel held out until 213 BC under Achaeus' widow Laodice and then surrendered.

Having thus recovered the central part of Asia Minor (for the Seleucid government had perforce to tolerate the dynasties in Pergamon, Bithynia and Cappadocia) Antiochus turned to recover the outlying provinces of the north and east. He obliged Xerxes of Armenia to acknowledge his supremacy in 212 BC. In 209 BC Antiochus invaded Parthia, occupied the capital Hecatompylus and pushed forward into Hyrcania. The Parthian king Arsaces II apparently successfully sued for peace.

Bactrian campaign and Indian expedition

Year 209 BC saw Antiochus in Bactria, where the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus I had supplanted the original rebel. Antiochus again met with success. [2] After sustaining a famous siege in his capital Bactra (Balkh), Euthydemus obtained an honourable peace by which Antiochus promised Euthydemus' son Demetrius the hand of one of his daughters. [3]

Antiochus next, following in the steps of Alexander, crossed into the Kabul valley, reaching the realm of Indian king Sophagasenus and returned west by way of Seistan and Kerman (206/5). According to Polybius:

- "He crossed the Caucasus (Hindu Kush) and descended into India; renewed his friendship with Sophagasenus (Subhashsena in Prakrit) the king of the Indians; received more elephants, until he had a hundred and fifty altogether; and having once more provisioned his troops, set out again personally with his army: leaving Androsthenes of Cyzicus the duty of taking home the treasure which this king had agreed to hand over to him."

Persia and Coele Syria campaigns

From Seleucia on the Tigris he led a short expedition down the Persian Gulf against the Gerrhaeans of the Arabian coast (205 BC/204 BC). Antiochus seemed to have restored the Seleucid empire in the east, and the achievement brought him the title of "the Great" (Antiochos Megas). In 205 BC/204 BC the infant Ptolemy V Epiphanes succeeded to the Egyptian throne, and Antiochus is said (notably by Polybios) to have concluded a secret pact with Philip V of Macedon for the partition of the Ptolemaic possessions. Under the terms of this pact, Macedon were to receive Egypt's around the Aegean Sea and Cyrene while Antiochus would take Cyprus and Egypt.

Once more Antiochus attacked the Ptolemaic province of Coele Syria and Phoenicia, and by 199 BC he seems to have had possession of it before the Aetolian, Scopas, recovered it for Ptolemy. But that recovery proved brief, for in 198 BC Antiochus defeated Scopas at the Battle of Panium, near the sources of the Jordan, a battle which marks the end of Ptolemaic rule in Judea.

War against Rome

|

|||||

Antiochus then moved to Asia Minor to secure the coast towns which had belonged to the Ptolemaic overseas dominions and the independent Greek cities. This enterprise brought him into antagonism with Rome, since Smyrna and Lampsacus appealed to the republic of the west, and the tension became greater after Antiochus had in 196 BC established a footing in Thrace. The evacuation of Greece by the Romans gave Antiochus his opportunity, and he now had the fugitive Hannibal at his court to urge him on.

In 192 BC Antiochus invaded Greece with a 10,000 man army, and was elected the commander in chief of the Aetolians. In 191 BC, however, the Romans under Manius Acilius Glabrio routed him at Thermopylae and obliged him to withdraw to Asia. The Romans followed up their success by attacking Antiochus in Anatolia, and the decisive victory of Scipio Asiaticus at Magnesia ad Sipylum (190 BC), following the defeat of Hannibal at sea off Side, delivered Asia Minor into their hands.

By the Treaty of Apamea (188 BC) the Seleucid king abandoned all the country north of the Taurus, which Rome distributed amongst its friends. As a consequence of this blow to the Seleucid power, the outlying provinces of the empire, recovered by Antiochus, reasserted their independence.

Antiochus mounted a fresh expedition to the east in Luristan, where he died in an attempt to rob a temple at Elymaïs, Persia, in 187 BC. The Seleucid kingdom as Antiochus left it fell to his son, Seleucus IV Philopator, by his wife Laodice.

|

Antiochus III the Great

Born: 241 BC Died: 187 BC |

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Seleucus III Ceraunus |

Seleucid King 223–187 BC |

Succeeded by Seleucus IV Philopator |

Notes

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Antiochus III "the Great" entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||